COUNTING THE LIGHT: A Post-Y2K Cosmic-Horror Americana

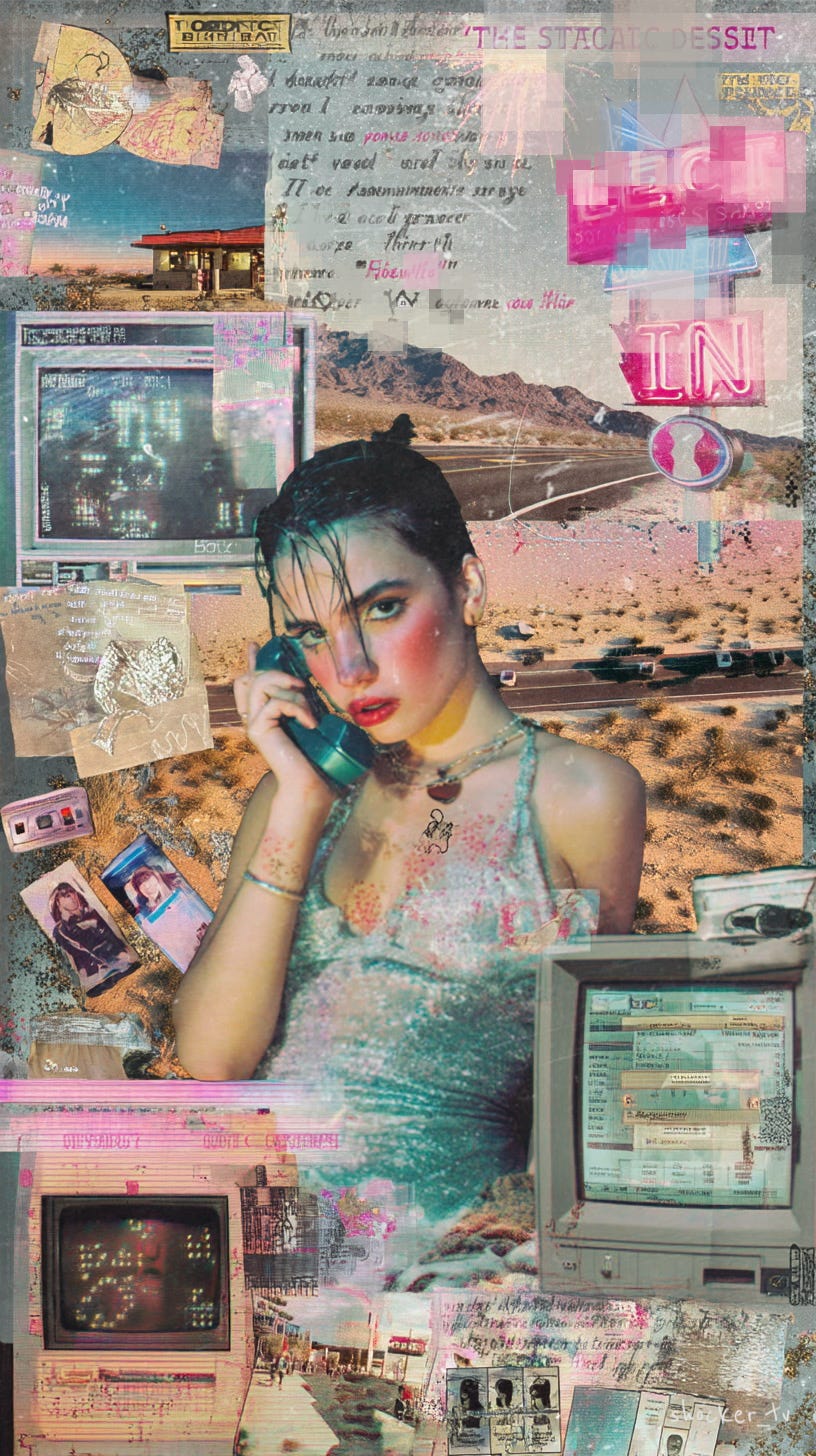

Book 1: The Static Desert (2005) Chapter One: The Year of Glitter Code

Static Road

The sky above Rachel flickered like a dying screensaver—angelic light looping through dust, searching for a signal that never quite returned.

It’s a skipped frame between one America and the next—half-loaded, half-erased. The highway hums like a VHS left on pause too long, the image burnt into the screen, color bleeding at the edges. There’s a sound to it: a high, trembling note that lives somewhere between a dial tone and a dying star. You could call it silence if you didn’t know better.

The Little A’Le’Inn sign blinks LI / IN / LI / IN, as if the neon itself can’t decide whether to invite or warn you. Nobody remembers when the last “E” went out. It’s just gone, the ghost of a letter floating somewhere in the static. Beneath the sign, a Coke machine hums with the same low, electric ache as the highway—sometimes it dispenses warm cans of Diet Rite, sometimes a single moth.

Gasoline Tom parks his truck beside it every morning, the bed rattling with fireworks and empty oil cans. He’s got a cigarette always stuck to the corner of his lip, unlit most days. “Independence don’t expire,” he says whenever anyone mentions the county ban. He’s a man who says things twice so they sound more like scripture. He runs his own illegal Fourth of July every other weekend—behind the diner, out where the sand gets glassy and the coyotes sound like women arguing in the distance.

Tom claims he used to work sound for a rodeo in Barstow, says that’s why he can hear “the difference between signal and soul.”

He once tried to explain to me that the radio static wasn’t random—that if you slowed it down, you could hear patterns. Morse code. Old call signs. Maybe even the voice of someone he used to love before she moved to Henderson and remarried a man who sold slot machines. “She still calls,” he told me once, squinting at the horizon. “Between stations.”

The locals call it the Glitter Code—the thing in the static that makes radios shimmer when the moon’s too bright. Sometimes the hum comes through car speakers or television sets left on Channel 3, filling the air like a slow electronic fever. It’s not music, but it makes you feel like you should dance anyway.

Earl Kleiber, my grandfather, swears it’s God clearing His throat through the CB. He used to sit out by the radio tower at dusk, the red light blinking on his face, drinking flat Tab out of the can and muttering like he was tuning himself to a higher frequency. “Frequency equals forgiveness, amplitude equals sin,” he’d say. “If you listen long enough, you’ll hear yourself apologizing.”

Maybe he was right. Or maybe it’s just leftover Air Force junk bouncing around up there, the afterlife of radar tests and forgotten launch codes. Some folks say the military built transmitters under the salt flats, machines meant to talk to satellites that never came back. When the wind’s right, you can hear the feedback—soft, like a woman humming through metal.

Either way, it hums. Every night, it hums. Sometimes it’s faint, like a memory rehearsing itself. Sometimes it’s loud enough to rattle the diner window and make the cat hide under the jukebox. There’s rhythm in it if you stay quiet long enough—like the heartbeat of something buried too shallow.

And the hum has rules. Everyone in Rachel knows them, though no one admits it. It grows loudest at exactly 3:11 a.m.—not 3:10, not 3:12. That’s when all the screens in town flash white for one second. CRTs, flip phones, even the old gas pump meter—all blink in perfect synchrony, like the synchronized eyelids of something half alive, half buffering.

Once, when I was ten, I woke to the flash and thought it was lightning. But the sky was clear, and the moon looked swollen, like it had swallowed a light bulb. My mother was asleep in the next room, hair spread across the pillow like an oil spill. I stood barefoot on the trailer floor, waiting for thunder that never came, listening to the hum gather under the walls like breath.

Now, years later, I still wake at that hour. Not from dreams exactly—more like from memory pretending to be a dream. Sometimes the hum sounds like voices underwater. Sometimes like music caught in its own echo. And sometimes I think it’s trying to remember us—the little town that learned to exist twice, once in sand and once in signal.

The Beautician of the Lord

Sister Darla runs her beauty shop out of a pink shipping container behind the diner, the metal walls sweating through summer like a body holding back confession. The paint’s flaked down to the bare steel in spots, but she covers the rust with stickers—angels, flames, glitter crosses, and one that says “JESUS SAVES, BUT TIPS ARE APPRECIATED.” The door creaks like a hymn when you open it.

Half her power comes from a stolen extension cord that disappears into the sand and reappears under the propane tanks behind Earl’s tower. The other half, she swears, comes from faith and Folgers instant coffee. She keeps a Bible next to the hair dryer, its pages clotted with loose hair and dryer lint, as if scripture itself were shedding. The sign above her door says “Wash Away Sin & Split Ends” in peeling cursive.

She baptizes her customers mid-rinse, one hand on the nozzle, the other making a sloppy cross on their forehead with the leftover conditioner. “The Lord prefers moisture,” she says, winking through a puff of perm steam. The women laugh and say “Amen,” though half of them don’t go to church anymore, unless you count the diner.

Her MySpace auto-plays a broken MIDI of “Jesus Take the Wheel,” warped like it’s been through a dozen resurrections. The melody stutters, gasps, then loops—holy, broken, ecstatic. Her page background is a tiled image of gold glitter with the caption “God’s Dust.” Every day she posts bulletins that read like chain letters and horoscopes for the damned:

IF U DYE UR HAIR UNDER MERCURY RETROGRADE U WILL REGRET FOR 7 YEARS.

VENUS IN GEMINI MEANS YOUR EX WILL TEXT (IGNORE IT, HE’S POSSESSED).

BLEACH IS HOLY BUT NEVER PURE.

Her followers—mostly truckers passing through, single mothers in Alamo, a man from Oklahoma who claims to see UFOs in his rearview mirror—comment with digital amens and low-res angel emojis.

Sometimes she live-streams from the shop using a webcam the size of a peach pit. The video freezes every few seconds, her face caught mid-blink or mid-prayer, as if God’s buffering her in real time. She says angels appear in the compression artifacts, the glitch halos flickering at the edges of her frame.

“I seen them,” she tells anyone who’ll listen, curling iron in hand like a weapon. “Hoverin’ above the desert like download bars stuck at ninety-nine percent. Waiting for a better signal.”

When power cuts out, she keeps working by flashlight. Says the Holy Spirit doesn’t need current, just current faith. She tells a story about how, during the blackout of ’03, she gave a full updo to a woman while coyotes screamed outside and the radio tower blinked Morse for “wait.” The woman’s husband died that night on the interstate, she adds softly, “but her hair held.”

Customers still come, especially the lonely and the almost-pretty. They say her blow-dryer smells like ozone and confession, that her touch feels like someone remembering your face. Darla calls everyone “sweet thing” and charges twelve dollars no matter the job. She believes tips are between you and God.

At closing time she sits on a plastic lawn chair behind the container, smoking menthols and brushing out mannequin wigs. From here she can see the whole town—tower lights blinking red, the diner sign twitching, the desert fading to static gray. Sometimes she hums along with the radio static, as if it’s a hymn only she remembers the words to.

When she’s tired, she talks to the mannequins. Calls them by the names of her old clients—Patty, Lorraine, CJ. Tells them about Mercury’s orbit, about how the sky’s gone silver with noise.

She says she once dreamed of the angels again, but this time they weren’t buffering. They were fully downloaded, wings made of LCD shimmer, voices pitched to the dial-up tone. “They was singin’ through the frequency,” she said, “and I swear one of ‘em had my face.”

Then she laughs like she didn’t mean it. Turns up the hair dryer until it drowns everything else out. The sound fills the desert, the same pitch as the hum—holy, broken, ecstatic—and for a moment, it’s hard to tell where prayer ends and interference begins.

Gasoline Tom’s Revelations

Tom lives in his truck, sleeps in the cab, and calls it The Embassy of Noise.

The name’s hand-painted across the driver’s door in shaky silver Sharpie, the kind that never dries right in desert heat. The interior smells of gasoline, fireworks, and motel soap. In the glovebox, he keeps three things: a pocket Bible missing half of Revelation, a tin of chewing tobacco, and a folded map of Nevada with circles drawn around radio towers like they were holy sites.

He sells fireworks, batteries, and secondhand dreams from the truck bed. You can buy a Roman candle, a car charger, or a story about the time he saw the sky open over Groom Lake and something blink back. He calls his stock “miracles per unit.” When the county bans fireworks, he says they can’t ban belief. “Freedom ain’t got a permit number,” he likes to remind anyone who asks too many questions.

Tom believes static is a language older than speech. He says God retired after inventing feedback. Once, he drilled holes in a tin can and strung it to the radio antenna, swearing it let him talk to “the ones who never logged off.” He keeps the can in the passenger seat now, dents and all, tied with twine. Calls it “The Receiver.” Says it hums when the moon is full.

His MySpace bio reads: “Recovering from silence.” He updates it from the diner’s computer every Thursday, posting grainy webcam photos of sunsets that look like nuclear tests, skies overexposed to the edge of obliteration. Captions read like revelations scrawled in dust:

BOOM = PRAYER.

STATIC IS MEMORY TRYING AGAIN.

IF YOU HEAR THE HUM, DON’T TURN IT DOWN. IT’S PRACTICING YOUR NAME.

People laugh, but they read every word. Even the skeptics, even CJ from the bar who pretends she’s too tired for desert prophecies. She told me once that Tom’s words made her fridge hum at night, that she started sleeping with it unplugged.

When the motel lights flicker, Tom takes it as a sign. He stands on the tailgate, cigarette in mouth, lighter raised to the sky, as if offering ignition to whatever might be listening. “If they’re out there,” he says, “they ain’t gone—they’re just buffering.” His voice is half joke, half sermon.

He says fireworks are the only honest language left: fire, flash, gone. Each one a syllable of light trying to remember what it was before combustion. He has names for his favorites: Bruise-Pink Saint, Teal Psalm, Ghost-White Bride. The sparks hang longer than physics allows, shimmering in impossible colors that make the air feel conscious for a second.

He claims the colors come from “borrowed magnesium from a crashed satellite.” Nobody checks, and nobody asks which crash. When they fizzle out, he collects the ashes in mason jars and lines them along his dashboard. Calls them “dead prayers in powder form.”

Sometimes he parks by Earl’s tower and tunes the truck radio between frequencies. He’ll sit there for hours, listening to the hum, the faint hiss of cosmic leftover chatter. “You ever think,” he says to no one, “that maybe this is the afterlife already, and we’re just the reruns?” Then he laughs, coughs, and turns the volume up until the static drowns him out.

Once, I found him asleep in the cab, headlights still on, radio whispering some scrambled CB sermon: “—and the light counted the living, one by one—” The words looped, glitched, merged with his breathing. I shut the door quietly and watched from outside as the truck lights dimmed like a heartbeat giving up.

In the morning he was back at the diner, sunglasses on, talking about how “the night told him something big was coming.”

“What kind of big?” CJ asked.

“The kind that don’t end,” he said, tapping his chest like it was a detonator.

When I think of Tom now, I remember the sound before the boom—the hiss, the inhale of light just before it burns. That’s the part he loved best. The moment when heaven and failure were the same sound.

Learning to Be Lonely in Public

By 2005, everyone in Rachel had two selves: one made of skin, one made of signal.

The first walked, smoked, sweated. The second hovered in dial-up purgatory, waiting for comments to load. You could almost hear the hum of the town’s second life—half static, half confession—rising from the trailers like electronic incense.

Earl Kleiber’s MySpace picture was the radio tower, captioned “listening.” He never posted anything else. Maybe he thought if he waited long enough, the static would start posting back. Sister Darla listed her mood as “divine buffering.” Her glitter-background page took two full minutes to load, angels spinning in circles like they were trying to ascend through bad bandwidth. Gasoline Tom changed his display name every week to strings of numbers—sometimes primes, sometimes coordinates. No one ever asked what they meant.

Even CJ—my mother, the woman who ran the bar and swore she’d never need another man or another modem—had a MySpace page that auto-played “Toxic.” It looped endlessly until the speakers gave out, leaving only a faint high whine, like the ghost of Britney still trapped in the wiring. Her profile quote read: “Don’t message me unless it’s real, or close enough.”

The town began to recognize itself on-screen, like a ghost catching its reflection for the first time. It startled everyone, then became routine. The waitress at the diner would check her notifications before refilling your coffee. Teenagers flirted in bulletins instead of words, each line tagged with a lyric, each lyric pretending not to hurt. The last functioning payphone was removed that spring; nobody noticed until someone tried to call 911 and the call rerouted to a “Network Error.”

Emotions got smaller. Easier to send. <3, :/, LOL. A whole language of mercy reduced to punctuation. The silence between posts became heavier than real quiet. People began performing sadness like karaoke, syncing tears to profile songs. There was something comforting in the repetition—uploading your loneliness until it looked curated.

If you drove through Rachel after midnight, you’d see the glow of monitors through every trailer window. Pale blue rectangles pulsing like votive candles for the living. Some houses flickered in unison, as if something behind the screens was breathing along. Out by the tower, the air smelled faintly of ozone, like God had brushed against the circuit.

CJ kept the bar open late for the lonely ones. They came not to talk but to type. Laptops open beside half-empty beers, typing in the dim light, faces washed in blue. The jukebox had died years ago, so they played music through their profile pages, overlapping into one metallic hymn—Evanescence, Nickelback, The Killers, Toxic. Everyone’s ghosts singing through everyone else’s ghosts.

I remember one night she looked up from wiping a glass and said, “You ever feel like the screens are watching us back?” I said maybe they were. She laughed, that dry kind of laugh that doesn’t need air. “Good,” she said. “Least somebody’s paying attention.”

Sometimes, the connection would drop all at once. Every modem light in town would blink red for a single second—3:11 a.m., same as the hum. When the signal returned, there’d be new friend requests waiting. No names, no pictures. Just blank profiles created at the exact same moment, each with a single line in the “About Me” section:

WE ARE STILL COUNTING.

No one admitted receiving them, but everyone did.

People deleted them, blocked them, then checked again anyway, as if the desert had decided to go online.

By that winter, even the coyotes had stopped howling. The silence outside grew cleaner, emptier, while inside every trailer, somebody was typing into the void, posting into the static, learning the new sacred art of being lonely in public.

And if you listened closely enough between keystrokes, you could hear it again—the hum returning, low and patient, like the desert clearing its throat to speak.